Sojourner Truth (1797–1897) was born into slavery but escaped to freedom and became one of the most noted African-American women speakers on issues of civil rights and abolition.

She was deeply religious and felt a calling from God to travel America speaking on slavery and other contemporary issues. At 6ft tall she was a striking presence, and used her powerful oratory to awaken the conscience of America to the injustice of slavery and discrimination.

Early life

Sojourner Truth was born to slave parents – James and Elizabeth Baumgree. She was born around 1797 and, at birth, was named Isabelle or ‘Belle’. Her family, including 10-12 siblings, were kept on an estate in the town of Espouses – 95 miles north of New York. When her Dutch slave owner, Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, Sojourner, aged nine, was sold for $100 to a new owner John Neely, who frequently beat her.

She was then sold between slave owners a few times, before moving to John Dumont of West Park, New York. Unlike previous owners, Dumont was more kindly disposed and her life improved somewhat, although she was harassed by Dumont’s wife.

Around 1815, Truth began a relationship with a slave from a nearby farm, called Robert. The relationship was strictly forbidden by Robert’s slave owner Charles Cation – because Cation would not own any children they had – but they met anyway. Unfortunately Cation caught the pair and severely beat his slave Robert. The beating was so savage that Robert later died from his injuries. The painful incident left a lasting legacy, haunting Truth throughout her life. Later she was told to marry a slave named Thomas, who was 20 years older than her. She had four children with Thomas and one child with either Robert or John Dumont.

Freedom from slavery

New York was one of the earliest states to begin ending slavery. The process was started in 1799, but slavery wouldn’t officially end until 4 July 1827. However, Truth became restless for freedom and after Dupont reneged on an offer to grant her freedom, in 1826, one year before the change in the law, she took her infant daughter Sophia and left Dumont. She found work as a domestic servant with the Van Wagenen family.

Despite the end of slavery in New York, Truth learnt that her five-year-old son, Peter, had been sold to Alabama where slavery was deeply embedded. With the help of her new employers, she took Dupont to court to claim he had sold Peter illegally. Truth won the case against her former slave owner and her son Peter was brought back from Alabama where he had been badly treated. It was a landmark case and the first time a black woman had won a court case against a white man.

This was an important time for Truth, free from the shackles of slavery; she had a religious conversion, becoming a devout, evangelical Christian.

She spent time with Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist, and also ‘Prophet Matthias’ who founded the Matthias Kingdom communal colony. When Pierson died, Truth along with others was accused of stealing and poisoning him. But the case was thrown out of court. Later Truth brought a slander suit against those who had made the false claims (the Folgers) and Truth won her second case.

Sojourner Truth

In 1843, Truth adopted a new name – Sojourner Truth (she had been known as Isabella Baumfree). The name reflected her new freedom, religious devotion and her acceptance of the Methodist religion. She later confided that, after her abusive life, her religious faith was a source of great solace.

“Jesus loved me! I knew it, – I felt it! Jesus was my Jesus. Jesus would love me always. I didn’t dare tell nobody; ‘t was a great secret. Everything had been got away from me that I ever had; an’ I thought that ef I let white folks know about this, maybe they’d get Him away, so I said, ‘I’ll keep this close. I won’t let any one know.'”

‘Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Bondswoman of Olden Time’, p 159.

She felt a calling to travel around America and speak about the realities of slavery and other forms of injustice. In her own words she said:

“The Spirit calls me, and I must go.”

Her religious faith was important for giving her the inner conviction to fight for justice, and if not successful in this world, she believed in the ultimate justice of God’s Creation.

“But I believe in the next world. When we get up yonder, we shall have all them rights ‘stored to us again.” (Anti-Slavery Bugle, Oct. 1856)

As well as abolitionist causes, Truth became more active in supporting women’s rights, religious tolerance, pacifism and prison reform. She joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Northampton, Massachusetts, which was committed to promoting the abolition of slavery and supporting women’s rights. Here she met other prominent abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. Although the group later disbanded she remained close to some of these prominent men and women.

In 1850, William Lloyd Garrison helped Truth to publish her autobiography “The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave.”

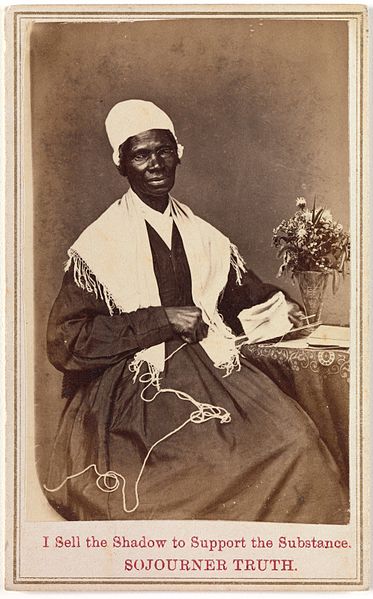

The book sold relatively well and the income from the book helped to support her travels and speaking commitments. She also sold small cards entitled “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

The book sold relatively well and the income from the book helped to support her travels and speaking commitments. She also sold small cards entitled “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

The proceeds from her book and cards helped her to pay for the mortgage on a house in the village of Florence, Northampton. She began to give more high profile speeches – often at women’s rights conferences. In May 1851, she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention where she gave a famous extemporaneous speech – later named “Ain’t I a Woman”. The speech demanded equal rights for black people and women. It was recorded by different members in the audience. When it was later published, it is likely her original words were embellished with southern phrases, which Truth wouldn’t have used – including the rhetorical question “Ain’t I a Woman” Nevertheless, the speech seemed to have created a strong impression on the audience and they were moved by her personal firsthand accounts of slavery.

“Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wan’t a woman! Whar did your Christ come from?” Rolling thunder couldn’t have stilled that crowd, as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with outstretched arms and eyes of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated, “Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothin’ to do wid Him.” Oh, what a rebuke that was to the little man.

Extract of speech by Frances Dana Gage published (May 2, 1863). version in the Anti-Slavery Standard (link)

Truth was also a good singer, and sometimes sang to audiences. At an abolitionist conference in 1840 in Boston, the great orator Wendell Phillips was marked down to speak after her. Worried she was not good enough to speak before him, she sang “I am Pleading for my people” to the tune of Auld Lang Syne.

Throughout the 1850s and 60s, she gave many speeches throughout the state – this was a time when public speaking was in high demand; in the absence of any radio or modern media, public speaking was a major source of information. The speaking circuit was mostly dominated by white men, so the presence of this imposing 6′ black woman was quite striking; her powerful words carried authenticity because she spoke from direct experience of slavery. She was also blessed with a powerful, low, resonant voice. She often travelled with her grandson, Sammy Banks who could read and write – this was a great help to the illiterate Sojourner.

Still it was a challenging role – fighting the double prejudice of the age – against both women and those of African-American roots. Like other female speakers such as Harriet Tubman, sometimes people were even sceptical that they weren’t really men. One apocryphal story relates that in 1858, someone interrupted a speech Truth was giving claiming she was a man. Truth responded by revealing her breasts.

Often audiences were quite hostile, with hissing and booing, even before she started. But Truth was able to adapt her speeches to the context of the time, and was adept at dealing with hostile audiences. As her reputation grew, her reception became more favourable. She was popular with like-minded abolitionists, though her insistence on the equality of women was radical even for some progressives. She also had a strong sense of humour and was willing to tease those who tended to a more self-righteous activism or were concerned with frivolous posturing.

“What kind of reformers be you, with goose-wings on your heads, as if you were going to fly, and dressed in such ridiculous fashion, talking about reform and women’s rights?”

(Narrative, Book of Life, p.243)

In 1856, she sold her house in Northampton and moved to Battle Creek, Michigan. In Michigan she continued to give speeches and lectures; she also widened her scope of political issues – speaking increasingly on prison reform and against capital punishment.

In 1856, she sold her house in Northampton and moved to Battle Creek, Michigan. In Michigan she continued to give speeches and lectures; she also widened her scope of political issues – speaking increasingly on prison reform and against capital punishment.

As well as speeches, Truth took part in direct action. In Washington she tried to force the desegregation of street cars by travelling in white only carriages. In the 1872 election, she sought to vote in the Presidential election, but was turned back at the polling booth. She also carried many petitions, urging people to sign for various causes, such as free land for former slaves. Speaking to people, she remarked wryly:

“Why don’t some of you stir ’em [the government] up as though an old body like myself could do all the stirring.”

During the civil war, she helped to recruit black troops and supplies for the Union army. She also sought to try and improve the condition of freed slaves in Washington D.C. Whilst in Washington, she won her third court case – a personal injury case after a street car incident.

After the civil war, she sought to encourage Congress to grant lands to freed slaves in the West. She argued that only when freed slaves had their own land, would they have the ability to support themselves and gain a real sense of dignity. Her efforts never persuaded Congress to take action.

“I am pleading for my people, a poor downtrodden race

who dwell in freedom’s boasted land with no abiding place

I am pleading that my people may have their rights restored”

‘Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Bondswoman of Olden Time’, page 303

For her works and public profile, she got to meet Abraham Lincoln and President Ulysses S. Grant.

In 1864, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation saw a major landmark in civil rights; it was one of the few solid political achievements Truth saw realised in her lifetime. It was not until 37 years after her death, a constitutional Amendment barred voting discrimination on the grounds of sex. It was the 1960s before voting rights for African-Americans were enshrined in law.

Increasingly frail, Truth died on 26 November, 1883, aged around 87. Though she liked to encourage the myth she was even much older ‘the oldest speaker on the circuit’ – was one phrase used. Her tombstone gives her age as 105.

In 2009, she became the first black woman honoured with a bust in the U.S. Capitol and in 2014, she was included in the Smithsonian Institutions list of the 100 most significant Americans.

No comments:

Post a Comment